|

|||||||||||||||

This page archives the various magazine and newspaper articles concerning "Darkside" in Orange County, including a review and photographs from the 1997 production. |

||||||||

O.C. Space |

||||

September 2005 |

||

Mission to the "Darkside" A fictional mission of Apollo 18 to the Moon is launched in Orange County by Michelle Evans

Yes, I understand the difference between the “Darkside” of the Moon and the “Farside” of the Moon. This appears to be a sticking point with many people familiar with the basic workings of our solar system, myself included. The darkside, of course, refers to whichever half of the lunar surface is not illuminated, while the farside is the half of the Moon that remains unseen by human eyes on Earth. Now that we have the definitions out of the way, let us proceed directly to the darkside.

Playwright Ken Jones penned “Darkside” over 17 years ago. It is a play made to be produced on a small stage with simple, blacked-out sets. In September 1997, Orange County got its first taste when the play was produced at the Huntington Beach Playhouse (see page 3 review). Many members of the Orange County Space Society were able to attend this first outing. Nearly everyone who came went away with a sense of having seen something rare and wonderful.

The story revolves, or should I say, orbits, around the last of the Apollo missions to the Moon, a fictionalized Apollo 18, that was supposed to launch in October 1973. Everything goes according to plan until the time comes to fire the ascent engine on the Lunar Module. Nothing happens. The two crew members are stranded on the surface, trying to extricate themselves from this situation with the help of Mission Control on Earth and their Command Module Pilot in orbit above them. We learn of events leading up to the mission through flashbacks in the mind of the CM Pilot whenever he is out of contact on the “darkside.”

It is compelling drama, but also includes lots of humor and a good dose of explanation on why humans must explore. This is certainly what drew me to the production and made me offer my services to the Rude Guerrilla Theater Company (RGTC) when I found out last fall that “Darkside” would again be coming to the OC stage in August 2005.

Sharyn Case, the original director from Huntington Beach, along with a couple of the actors from that production (Vince Campbell as “Gunner” Smith and Larry Scott as reporter Robert Hughes) definitely proved that this would be a quality endeavor. I was anxious to help out in a technical capacity in order to lend whatever authenticity I could to this purposely sparse stage. Sharyn was very enthusiastic to have me aboard, and I was constantly surprised at how willing everyone was to make the play as technically accurate as possible within the confines of the drama.

My first day was on the final evening of casting. The RGTC works out of the Empire Theater in Santa Ana, which seats only about 40 people in a packed house. I entered the theater and sat mesmerized by the different actors going through the same scene over and over again, each with a different take on how to perceive their character. When it was all said and done, we all agreed that enough quality actors had been seen to cast the play at least twice with superb talent.

Besides those from the original cast, we ended up with Jonathon Mackanday as CapCom Simon Lunney, Jay Fraley as CM Pilot Bill Griffin, Ryan Harris as Lunar Module Pilot Ed Stone, Coreen Mueller as Beth Griffin, and Jami McCoy as Gigi Stone. Each proved extremely capable in their roles, bringing nuances I would never have thought from just reading the script.

To me, one of the hardest parts to play had to be CapCom. Jonathon sat alone at his desk throughout the play, but we believed he was part of a large contingent at Mission Control from the first moment he walked on stage to shake hands with his (nonexistent) fellow controllers and proceeded through the countdown checklist.

Every actor must be recognized for all they brought to their roles. Jay circled the Moon endlessly and gave us a glimpse inside the dark recesses of his mind as we delved into the mission and its consequences. Ryan teetered on the edge with his unseen fears and outwardly cocky fighter jock mentality. Vince played father to his rookie crew, explaining what they will experience in space and dealing with an emergency that ultimately cannot be dealt with. Larry served up the right mixture of the self-assured reporter who wanted to ask the hard questions of a program he might not have fully supported.

To counter the boys’ club, Coreen and Jami brought polar opposites to their portrayals of the astronaut wives. Jami was lost without her husband, who has dedicated his life to being The Perfect Astronaut. To compensate, her character fought for a way out, knowing she had to distance herself from her husband even before the possibility arrived of his ultimate demise. Coreen played the supportive wife of the Command Module Pilot, knowing that even though he had the best chance of survival on a very dangerous mission, whatever the outcome, this is the last of the Apollos and her husband will be out of a job, even if everything goes perfectly.

On the production side, Cynthia Huyck was irreplaceable as the Stage Manager, Heather Enriquez supplied great costumes, Kristina Seitz was the Assistant Director and flawlessly worked the technical board during the play, and Andrew Nienaber provided the evocative lighting.

served a dual role in the production. First and foremost, I was the Technical Advisor. However Sharyn also wanted to give me time on stage. To this end, I decided to honor Guenter Wendt. Guenter is the man who put the astronauts into their spacecraft and sealed them up before each mission. I even had the costume designer Heather Enriquez find me a bow-tie so I could emulate his style at the launch pad.

During the prologue for “Darkside,” I entered the Command Module Independence to check systems prior to crew entry. I then strapped them in and sealed the hatch for launch. Later, I also had a literal walk-on part to place a bench used by the astronauts for their pre-launch press interview. These times on stage were exciting. I am only glad that I had no lines to remember so I didn’t have the possibility of screwing things up with all these consummate actors surrounding me.

Live stage is unique. You would think it could get boring, going back and doing the exact same lines and scenes over and over each night. No two performances are ever the same. We had many patrons who came back on several occasions to watch different performances that could attest to this fact. An example was during one performance where a light cue went out early when I was supposed to retrieve the press conference bench. Instead of light to guide my way, I had to locate and remove the bench in total darkness, trying all the time not to knock anyone down wielding this unwieldy piece of furniture. We all survived to fly another day.

Ken Jones wrote a marvelous script that really gets across the feelings, beauty, and sometime stark terror, that can be spaceflight. There were some details that he missed and that only an obsessive-compulsive space nut such as myself would catch, let alone worry about. Sharyn brought me in to do what I do best, nit-pick the technical details. I did my job and, almost without exception, the entire cast and crew accepted my input and did their best to get it right.

In addition, I supplied many small props such as checklists for the crew, a Flight Operations notebook for CapCom, and special badges for those who needed them for NASA access.

The thing of which I am most proud (besides being a part of this fabulous cast and crew) was the design of the Apollo 18 mission patch with Bob Kline. These proved extremely popular as souvenirs and even made some money for RGTC and OCSS.

For two months before we opened, the cast rehearsed and perfected their parts. You can view their progress on my web site at www.Mach25Media.com. It was an amazing phenomenon to watch unfold.

On August 5th, opening night arrived. Not only did it coincide with Neil Armstrong’s 75th birthday, but also with my 50th. My wife, Cherie, arranged a surprise party that included friends coming from hundreds of miles away. It was a fantastic way to spend a birthday, to be surrounded by friends at the premiere of a spectacular production about the wonders of space exploration. I must take this opportunity to thank everyone associated with that memorable night.

Being behind the scenes, peeking through the curtains to see the performances, watching the reactions of the actors as they completed a scene and went offstage, are all priceless memories. “Darkside” will never be forgotten. I hope that it returns to Orange County soon. For those of you not in the local area, seek out local theaters and put in a good word for them to mount a production of their own. XXXX |

||

O.C. Register |

||||

12 August 2005 |

||

Probing the "Darkside" of Space Travel Ken Jones' gripping drama takes us to the moon, and to the inner lives of U.S. astronauts. review by Eric Marchese

Even if the problems plaguing NASA's space shuttle mission hadn't been so prominent in the news of late, Ken Jones' "Darkside" would be no less gripping.

Could anyone other than an astronaut fathom the sort of mental and emotional compartmentalization required to undertake anything as hazardous as space exploration, then regard it as routinely as just a job to be done?

Jones studies that mindset by examining the three-man crew of the fictional Apollo 18 mission: a captain assigned to orbit the moon in the spacecraft Independence and his buddies, the mission commander and another captain sent to explore the moon's surface in Yorktown, the lunar module.

At Rude Guerrilla Theater Company, director Sharyn Case travels a familiar road with a script, and many of the same cast members, she directed in the tale's West Coast premiere at Huntington Beach Playhouse in 1997. Rude G's black-box Empire Theater staging is more intimate, so that much more compelling. We can see into the faces of these men as lines of concern and, on occasion, fear, are etched into their normally placid features.

It's October 1973, and Jones asks us to imagine that the Apollo program, whose last mission, Apollo 17, was in December 1972, has continued.

Onto this what-if scenario Jones grafts a worst-case outcome: When it comes time for the module to blast off and re-dock with the spacecraft, its ignition and thrusters misfire. Mission control is at a loss. The astronauts are in danger of being permanently stranded, while their crewmate anxiously orbits above, gripped with loneliness - especially when he orbits the moon's dark side.

Jones uses flashbacks to give us crucial moments leading to the moon shot and the crisis; the 1989 script is a witty, well-crafted mixture of sci-fi, drama and suspense, with plenty of humor to break the tension. "Darkside," though, is as much a psychological study of three diverse temperaments as it is an adventure tale of space exploration

On the surface, the crew — Capt. Bill Griffin (Jay Michael Fraley), Capt. Ed Stone (Ryan Harris) and Commander Gerald "Gunner" Smith (Vince Campbell) - display jocular confidence. During flight simulations, though, Bill has helped calm the panic-stricken Ed, while trying to allay his own fears regarding the mission (waiting for liftoff, he says, is like sitting atop "a 36-story stick of dynamite") and the prospect of orbiting the moon, alone, for days at a time.

A scene on the beach, weeks before the launch, contrasts the exhilaration Gunner feels about moon missions ("It's like Genesis and Armageddon all rolled into one!") and first-timers Bill and Ed's trepidation. Bill and Gunner belatedly realize that Ed could crack at any minute, and therein lies much of the script's suspense.

Harris credibly mixes Ed's vulnerability — the mounting terror and panic just below the surface - and the phony calm front he puts up. Campbell nails Gunner's toughness and cool professionalism. Nothing rattles this guy, who regards poking around on the moon as all in a day's work — yet he hasn't lost his awe of the infinite beauty of space.

Bill's skin is dangerously thin, and Fraley invests him with a burning resentment at being perceived by outsiders as "safe" from danger for never having to leave the ship. Fraley shows how Bill's easygoing swagger is a facade for his ambivalence and his suffocating sense of guilt once his friends become stranded.

Jami McCoy and Coreen Milstein Mueller are the lonely, neglected wives. As Ed's wife, Gigi, McCoy has the more complex role, drinking heavily, flirting with Bill - anything to get Ed's attention. Mueller's Beth is at first depicted as the supportive, dutiful wife to Bill. Like Gigi, though, she feels shut out. The characters may seem cliché-ridden, but they must ring true to any woman whose husband was ever married to his career.

Jonathon P. Markanday is a quietly competent head of mission control, and Larry F. Scott is credibly pushy as a reporter who goads the crew at every turn, intent upon finding a chink in the mission's armor.

Case's staging divides the black-box set into separate areas, and her soundtrack is enjoyably rife with moon-themed pop tunes such as "Blue Moon" and "Bad Moon Rising." The backdrop is Fraley's set, a gray-white moon painted against all-black wall and floor, while [Michelle] Evans' technical advisement and Heather Enriquez's costumes — flight suits for the astronauts, gauzy gowns and '60s 'dos for the women — provide a level of authenticity. XXXX |

||

The Star-Progress |

||||

12 August 2005 |

||

"Darkside" is Highlight of Guerrilla's Season Ken Jones' gripping drama takes us to the moon, and to the inner lives of U.S. astronauts. review by Anne-Margret Bellavoine

NASA's Apollo lunar exploration program ended in 1972 with its final, 17th mission. Thus Ken Jones' 18th mission is a fictional narrative.

Jones' compellingly stark drama, directed by Sharyn Case, documents this final voyage, starting with two astronauts stranded on the Moon, Vince Campbell as Commander "Gunner" Smith and Ryan Harris as Pilot Ed Smith.

The two are attempting to lift off from the lunar surface again, with pressure problems preventing the operation.

Meanwhile, Captain Bill Griffin (Jay Michael Fraley) is circling alone in the space ship above, leaving and entering the dark side with each rotation.

Houston, personified by Jonathon P. Markanday as Cap-Com, is providing reassuring advice and data analysis from Houston through space communication.

The story is told through a series of flashbacks during the time preceding the launch, with the three astronauts training and living their lives while waiting for their approaching historical moment.

If Gunner's character is surprisingly left unexplored, the one minor weakness in an otherwise near flawless drama, the other two men's personae are defined through their wives, solidly rooted Beth (Coreen Milstein Mueller) and out of control Gigi (Jami McCoy).

While Beth is Bill's anchor, providing smooth serenity through the vagaries of life as an astronaut's wife, Gigi cavalierly ignores Ed while relentlessly pursuing Bill.

Jay Michael Fraley's austere moon painting provides an eerie backdrop for the [unfolding] drama, with a few black boxes and tables providing the suggestion of the various other locales, from space capsules to bed and bar rooms.

Nerves and resolves erode when oxygen and time begin their ultimate countdown to disaster, and flawed humanity regains its survival urges at odds with the hero and glory worship of astronauts viewed as modern gods.

This compact play, humorous as it explores the frontiers of mind and space, is a highlight of the local season. The current Space Shuttle missions' revival, whose issues mirror Apollo's, makes it a must-see. XXXX |

||

O.C. Weekly |

||||

19-25 August 2005 |

||

Rickety Rocket Ken Jones’ tense Darkside aims for the moon, gets stuck on Earth review by Joel Beers

Space exploration and theater don’t have the most intimate of histories—and not just because we’ve been sending humans into space for 50 years and onto stages for 3,000. The canvas for space exploration is nothing less than the universe; a theater set is rarely bigger than your living room.

Ken Jones’ 1987 play Darkside is one of the rare theatrical forays into the final frontier. At its best moments, this Rude Guerrilla production shows that theater’s greatest asset—the power to prod the imagination and convey dramatic emotion through words rather than visual stimuli—can work even when it comes to space travel. The play vividly captures the intense tension and loneliness of two men trapped on the surface of the moon while their fellow astronaut, helplessly orbiting around them, desperately waits for a successful lunar launch that will unite them with his module so they can successfully return to Earth.

On that level, the play and production work. And if Jones had focused on merely our three astronauts-in-crisis, Darkside could be a great play. But apparently feeling he didn’t have enough to work with, he hamstrings the soaring action and frequently eloquent poetics of his play with soap opera histrionics, told through a series of flashbacks intercut with the rapidly failing mission. The cheap infidelities, domestic squabbles, black-hatted journalists and implausible circumstances—such as a space program that apparently doesn’t conduct rigorous enough psychological examinations to realize that one astronaut is prone to critical-mass emotional breakdowns—can sometimes make Darkside feel like Dallas dry-humping Apollo 13. The result is an ungainly, unsatisfying construct that makes you wish Jones had hit the delete key on every scene not set in space.

Still, Darkside ultimately delivers, thanks to some stellar acting by Jay Fraley, Ryan Harris and, particularly, Vince Campbell, who gets the most defined character and the best lines. When Campbell explains that space exploration is valid and important because it’s the logical progression of humanity’s inherent drive to redefine itself through movement, you might not agree with the politics—can’t it also be seen as humanity’s inherent drive to dominate and subjugate everything within its grasp?—but you feel the passion. Likewise with his articulation of what everyone who’s ever seen this planet from outer space must surely feel: that heaven and earth have reversed themselves. It’s like looking into God’s face, he says, in a moving blend of science and poetry that skirts the eschatological and recalls the psychedelic hues of Robert Hunter’s lines in the Grateful Dead’s “Eyes of the World.”

The greater consciousness and awareness that exploring space affords are in constant conflict with the passions, pettiness and other flaws of the characters in Darkside. Had Jones been able to express them without resorting to ham-fisted, melodramatic, all-too-terrestrial dialogue, or had this production been able to deliver them more subtly, this play could be riveting rather than rickety. XXXX |

||

O.C. Space |

||||

November 1997 |

||

|

|

|||

|

||

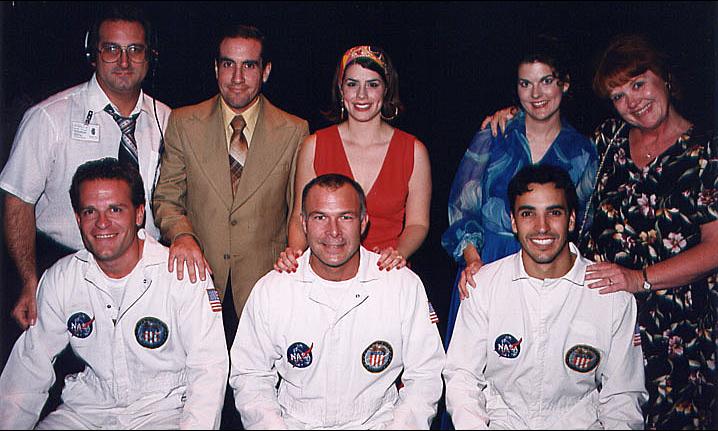

The photos with this review were taken by Michelle Evans at the original Huntington Beach Playhouse production in 1997. A larger cast photo is at the bottom of the review. |

||

Examining the "Darkside" of Apollo review by Michelle Evans, November 1997

A burst of static. The Earth falls below the lunar horizon as Apollo 18 enters the farside portion of its orbit. Aboard the Command Module Independence, pilot Bill Griffin has just become isolated from the rest of humanity. No contact with Mission Control. No contact with his fellow astronauts on the lunar surface. Nothing penetrates the grey, cratered, lifeless world he glides over. Griffin stares at his controls, then looks out the window. Whatever he sees, there is no one to share his thoughts with. He drifts into a fitful sleep.

Through Bill Griffin’s dreams we flashback through the mission, the last of the Apollos. His fellow astronauts, Mission Commander Gerald R. “Gunner” Smith, and Lunar Module Pilot Ed Stone flawlessly carried out their exploration of the surface only to be stopped short of triumph when the Yorktown fails to launch from the Moon, to rendezvous with the Command Module, Independence. They are now trapped on the surface with air running out and options quickly dissipating.

This is the story of the play “Darkside” that appeared in September at the Huntington Beach Playhouse. When I first caught a mention of the production in the newspaper, I was fascinated by the fact that someone would be able to make a play out of an Apollo mission. Trying to capture the essence of a Moon landing in a fictional flight would be a difficult undertaking.

The logistics alone of putting together believable sets would be a daunting task. They decided to let the best set designer in the world have the job: the audience’s imagination. The entire play takes place on a blacked-out set. Three black cubes serve as seats in the command module, two cubes on a riser make the lunar module. Stage left is the only real hardware visible: a chair and a small computer screen recreates CAPCOM, the Capsule Communicator, at Mission Control.

Each time we regain communication between the CM, LM, and CAPCOM the story moves forward with everyone’s attempts to rectify the anomaly and get the astronauts safely home. Each time communication is cutoff on the farside of the Moon, we enter the darkside to understand the people we are hoping to save.

At a prelaunch news conference a reporter, Bob Hughes, hounds Bill Griffin about the jealousy he must feel toward his crewmates who actually get to walk on the grey dustball. Just how far should the press be allowed to pursue someone’s personal feelings?

A party finds us watching Ed Stone’s wife, Gigi, take a few too many drinks and become a little too friendly toward Bill, while she expounds on how her husband will die on the Moon, pursuing the perfect rock sample. Does the wife who thinks she is being left behind have the right to look after herself?

A ride in the Apollo simulator shows that Ed may not be truly suitable to fly because he might break down during an emergency. Only Bill knows of the problem and decides to protect him since he believes that as a scientist, Ed has more of a right to go than anyone. We find out in another flashback that Bill’s attitude may be more based on a guilty conscience than any altruistic motives. In the end, however, it is their friendship which rules their emotions.

I felt the play succeeded fantastically in putting us into the minds of the characters and taking us to the Moon. Some complaints that I heard voiced were that since it dealt with what becomes a tragedy, “Darkside” puts the Apollo program in a negative light. Another was that Stone would have never made it through training with his stress-related problems. We find this does lead to their ultimate demise.

My response is that what we saw portrayed on stage could have easily happened in real life. Technical flaws and a feeling of nothing can go wrong, cost the Apollo 1 crew their lives. We nearly lost three more astronauts on Apollo 13. Physical problems with a crewmember could just have easily been a factor. An excellent example is that during the X-15 program pilot Mike Adams was cleared for high altitude flight even though medical tests proved that he was susceptible to vertigo. The first time he left the atmosphere the vertigo appeared and he ended up losing his life when the aircraft broke apart during reentry.

Contrary to the NASA public relations hype of the 60s and 70s, astronauts were real people, neither supermen nor robots. “Darkside” captures not only the tragedy of a failed mission, but also the camaraderie and humor between the men, as well as the awe of their magnificent undertaking.

When Griffin complains that he feels unneeded in lunar orbit while his crewmates try to fix their problems on the surface, they fire back with the retort: “My clean underwear is with you... how much more needed do you want?” Or even a simple comment as he rounds the Moon yet another time: “I'm getting ready to go bye-bye.” CAPCOM replies: “We copy bye-bye.”

A last fling at the bar before launch has the two rookies asking Gunner what it’s really like to ride a Saturn V into space. His description eloquently puts you in the Apollo, on top of that 36-story stack of explosives. “Out of an ocean of fire, you climb.” When the words start to fly between Gunner and Ed about the best way to handle the emergency, Bill fires back: “Thank god there’s not much gravity down there with all the weight that's being thrown around.”

Ed finally convinces the commander that their best option is to go EVA and eyeball the problem from the outside. He dons his imaginary spacesuit and exits the Lunar Module. What is it like to walk on the Moon? Just watch the sequence with Stone walking in slo-mo and singing “Day-O!” That simple sequence conveys more of the feeling of spaceflight than any sanitized NASA report or film ever could.

We see Ed’s final break with reality a split second before the commander. The tingle in my spine told me to jump on stage to help Gunner stop the catastrophe, but there is nothing to be done.

Griffin loses contact and even when he must know what it means, he doesn’t let it register that it is not just an equipment glitch. He calls repeatedly on the radio, wanting to drop to the surface and grab his colleagues and friends back from the irrevocable end. CAPCOM desperately tries to get through to Griffin, who appears to have lost any reason to return home. The drama of unreasoning despair.

“Darkside” did what it was meant to do. For an hour and a half, during two weeks of shows, each packed theater was transported to the Moon. We felt the joy and the anguish of a lunar mission that never was.

It has recently been learned that NASA did not fight the cancellation of the last Apollo flights because they truly felt that each time they went, someday luck would run out and a crew would be left behind. They felt it wasn’t worth the continued risk. But risk will always be with us. The true darkside of our space program is our lack of boldness. The timid accomplish nothing. XXXX |

||

|

||

Top Row (L-R) Paul Castellano (CapCom), Larry Scott (Reporter), Ruth Berowitz (Gigi), Molly Kincaid (Beth), Sharyn Case (Director).

Bottom Row (L-R) Apollo 18 Flight Crew Kevin Deegan (Command Module Pilot, Bill Griffin), Vince Campbell (Mission Commander, "Gunner" Smith), and Michael Piscitelli (Lunar Module Pilot, Ed Stone) |

||