|

|||||||||||||||

“Into that Silent Sea” A review of the first volume in an ambitious new series about human spaceflight by Michelle Evans, July 2007

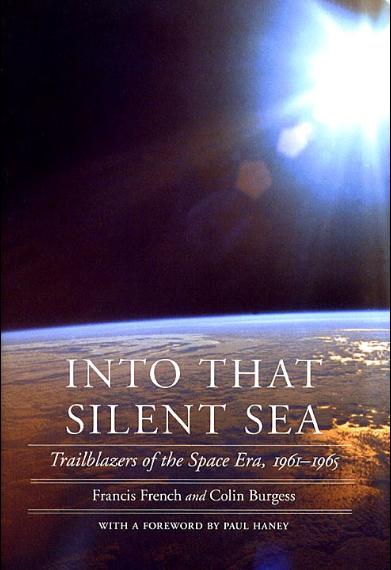

Samuel Taylor Coleridge provides the quote that lends its name to the first of a planned ten-volume series chronicling the Space Age. I believe that Francis French and Colin Burgess have chosen well, as Into that Silent Sea, Trailblazers of the Space Era, 1961-1965, is one of the most evocative titles about flying into space I can recall. A good title certainly tells a lot about a work, and this is especially true in this case.

Most of us aficionados of the 1960s Space Race feel we know the story inside and out. We can often recite trivial facts and figures, and we know the names of every astronaut and many cosmonauts on the way to the first lunar landing and beyond. Height, weight, and thrust of a man-rated booster is no problem, as is the current location and disposition of the spacecraft that took these men and women to space and back.

For my own part, I have had a passion for this since I first had awareness of the outside world and the universe beyond. I would consider myself a knowledgeable person when it comes to all of this, yet the authors of Into that Silent Sea can show us all a thing or two (and a lot more) about the most important aspect of this quest to become a spacefaring race—the human beings who made it all happen, not just the people on top of those rockets blasting into space, but those that stood alongside them, and even a few who just dreamed of doing so.

The overarching title for the series is Outward Odyssey: A People’s History of Spaceflight. Based on this first volume, we will learn a lot about the back story of those people beyond what I have seen before elsewhere. The great thing is that it will not just focus on the American space program, but the Russian as well.

Into that Silent Sea trades between these two sides of the superpower race to the Moon, giving us a wonderful behind the scenes glimpse from Yuri Gagarin’s first foray into the cosmos to the harrowing spacewalk of Alexei Leonov, from the competition to be first at Cape Canaveral to limping through a day in Gordo Cooper’s dying Mercury capsule.

Burgess’ and French’s two writing styles mesh easily, and the book speaks with one authoritative voice. The space travelers and others written about in the book have shared their stories and given us all a peek beyond what we are used to seeing.

One aspect that stood out for me was the stories of the women on both sides of the curtain: the Mercury 13 women, who answered the call to see if a female could withstand the same rigors as those famous Mercury 7 astronauts, and the story of Valentina Tereshkova, who did accomplish what her American counterparts only dreamed of doing.

Having read much about the American women tested by Dr. Randy Lovelace, I have to say that this book presents the best researched analysis of the situation. We often decry the ability for these women to have flown in space, and always saw those who opposed their flight as being on the wrong side. Yet here, the authors draw upon a close relationship with Mercury 13 participant Wally Funk to present an unvarnished version where we learn first-hand how their plight may have been undermined by those closest to the Women in Space program.

Yes, the women passed the tests given to them, but they never had the opportunity to go through the entire medical and psychological regimen the men were forced to endure. The fact that Dr. Lovelace ran these tests without NASA’s knowledge or consent, and then presented the women out of left field as fit to fly, certainly did not help his case with the administration. The largest impediment to the women was their lack of jet pilot experience. NASA is blamed for this short-coming in many reports, yet it was the military at the time that prevented women from entering this high-stress field.

Even though many of the Mercury 13 were pilots, the lack of jet experience was a major factor when you understand the fundamental differences between flying a Cessna and zooming at supersonic speed in a Super Sabre.

This was highlighted to a certain degree when you read the authors’ account of Tereshkova’s flight. Valentina was an accomplished parachutist, but again had no jet flight experience, and, according to many accounts, the discipline needed for that occupation pays off in spaceflight, which Tereshkova did not show when she was possibly unable to complete many assigned tasks while on orbit.

In the end, what ended up being a stunt for the Soviet Union by being first in space with a woman, may have helped the Americans in the race for the Moon. President Kennedy had set our goal, and one of the primary reasons that emerges for the fact we didn’t fly a woman into space is that it would have distracted us from that single-minded goal. The Soviets, on the other hand, were primarily interested in upstaging us at every turn, thus sabotaging their own efforts by not concentrating on the areas of more importance.

This is the type of juxtaposition we see throughout Into that Silent Sea. It is a unique work in that it presents both sides of the race in a clear and succinct manner while giving us real astronauts and cosmonauts, many never before discussed in Western press. The closest comparison would have to be Two Sides of the Moon, by Dave Scott and Alexei Leonov. However wonderful that book is, it doesn’t compare with the French and Burgess work in that we examine many more spacefarers than just the one American and one Russian, and put it all in the context of the flights as they occurred.

Beyond the astronauts and cosmonauts, we also meet many other significant players along the way; people often overlooked, and yet critical for the way the story unfolds.

If I have to find fault with the work, there are two things that come to mind. First, is the lack of an index to aid in searching for the people and incidents that interest us the most. Second, is the paucity of photographs. The space race was a visual feast, in that it showed people racing above the planet, yet most of the photos are simple head shots of the people talked about in the text. Most people today have probably never even seen one of the grainy shots of Leonov’s first-ever spacewalk, so things of that nature would have added immensely to the impact of the book. I hope that in future volumes, more effort will be made to include historic and little-seen photos to illustrate the text.

We’ve read stories and seen movies, documentary and otherwise, that have supposedly told us the inside scoop. As the first in the Outward Odyssey series, I believe Into that Silent Sea will be viewed in the future as the one that led the way to what could prove to be the definitive story of the people involved in our rise to the challenge of spaceflight. XXXX |

|

|||